Week 1 : Introduction to Python¶

Outcome: Students will be able to perform simple calculations with Python

- What we will do:

Setup: Install Anaconda and get familiar with Spyder

Variables & primitives

Doing simple algebra

Exercise: Python as a calculator

Lists in Python

Setup¶

You will need to install Anaconda Python on your PC by following the instructions at https://docs.anaconda.com/anaconda/install/windows/. If you are not using Windows, Google for “Anaconda Python installation on <Mac OS or Linux>” and follow the procedures.

- While you go through these two things, we’ll talk about:

- What this course is about

- What is coding

- What is Python

- Overview of what you can expect

Spyder¶

The most important thing we need to run Python code is the Python interpreter itself. We can edit Python code in any text editor. However, it helps to have the assistance of an Integrated Development Environment, or IDE, especially for beginners. For the purpose of this course, we will be using Spyder, which comes installed with Anaconda Python. (If you already know what an IDE is, feel free to use your favourite option!)

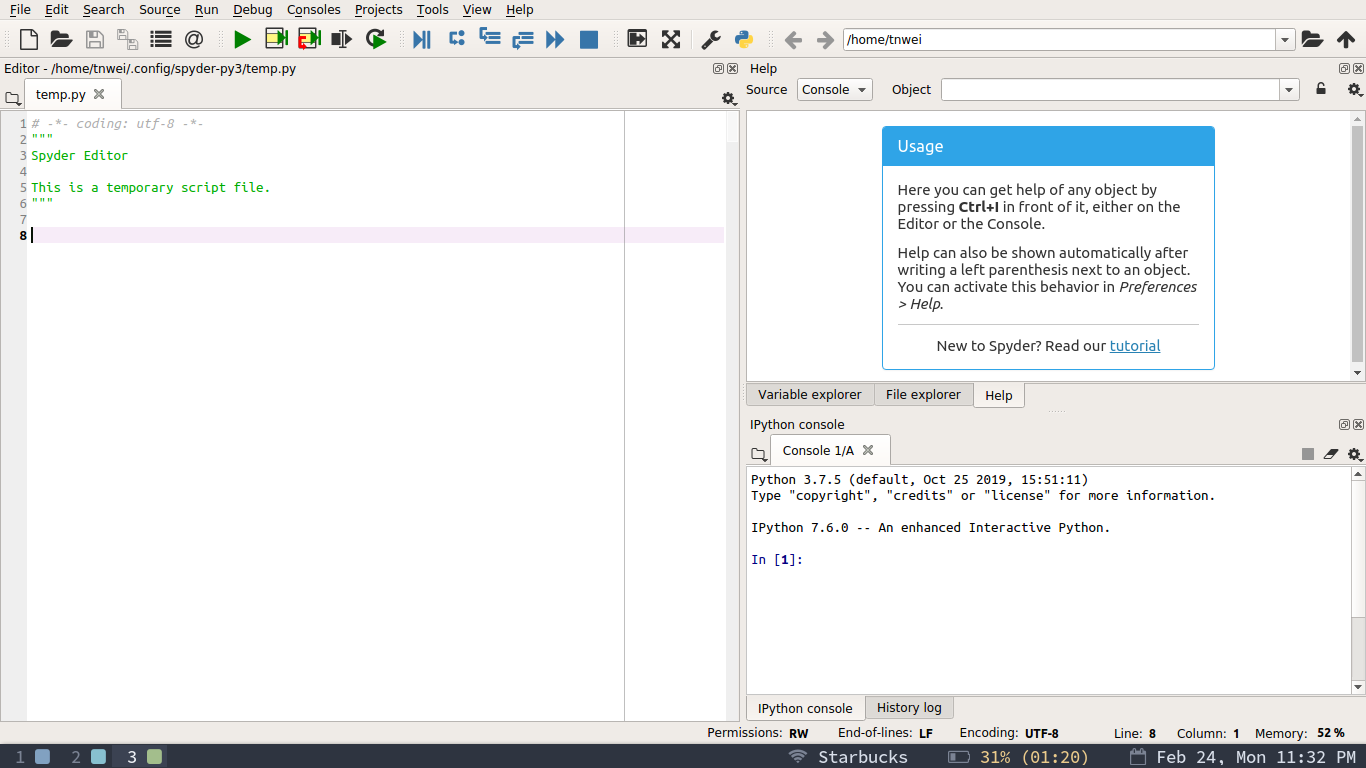

We begin by launching Spyder. If you are on Windows, search for Spyder in the Start Menu. Once Spyder has fully loaded, you will see something similar to the interface below.

This is what you should see after Spyder is launched.¶

First things first, take a look around Spyder, under Help –> Interactive Tours –> Introduction tour. Spyder will briefly introduce the windows in your workspace.

Hello World¶

We will now get started with coding by writing your very first program, Hello World. It is a classic first program for beginners to code, originating from programming books in the 1970s.

In the code editor, type in the exact phrase below:

`print('Hello World!')`

Press F5 to run. You should see the output Hello World! being displayed in the IPython console. You have just run your very first program!

(If this is your very first time running code in Spyder, Spyder will pop up a little menu asking you about options for running files. Just press Yes and move on.)

print¶

The print() statement in Hello World allows you to output to the IPython console. In the older days, computers physically printed their output on paper, thus the term ‘print’. Go ahead and replace “Hello, World!” with “Goodbye, World!”, and run the code again. You should see the console output change to Goodbye, World!”

Variables & primitives¶

Variables¶

In Python, we use variables to store values. Let’s do “Hello, World” again, but this time, type the following:

a = 'Hello, World!'

print(a)

a is a variable. It represents ‘Hello, World!’. Notice that print(a) returns the same thing as print(‘Hello World’). We assign ‘Hello, World!’ to a using the equals sign.

Now, if you do the following:

b = 1234

c = 1234.0

d = True

e = False

f = 'True'

g = '1234'

print(b)

print(c)

print(d)

print(e)

print(f)

print(g)

You should see the following output, where the corresponding values assigned to the variables are printed:

Hello World

1234

1234.0

True

False

True

1234

We see three sets of 1234 in the output. However, they DON’T all represent one thousand two hundred and thirty-four. Let’s see why.

Primitives¶

Values in Python have multiple data types, revealed by typing type(variable). You could check the data types for the variables from before by running:

print(type(a))

print(type(b))

print(type(c))

print(type(d))

print(type(e))

print(type(f))

print(type(g))

But to make it easier to visualize, print the variables before the type instead like so:

print(a, type(a))

print(b, type(b))

print(c, type(c))

print(d, type(d))

print(e, type(e))

print(f, type(f))

print(g, type(g))

Look at your output:

Hello, World! <class 'str'>

1234 <class 'int'>

1234.0 <class 'float'>

True <class 'bool'>

False <class 'bool'>

True <class 'str'>

1234 <class 'str'>

Notice that there’s 1234 with <class ‘int’>, <class ‘float’> and <class ‘str’>.

- Briefly explaining each data type one by one:

int: Integers, from -infinity to positive infinity

float: Floating-point numbers, any rational number within limit

bool: Boolean i.e. True / False values

str: A sequence of characters, in other words, a string.

- To keep things simple, just remember them as such:

Integers are any whole numbers with no decimal points

Floats are any numbers involving decimal points

Booleans are any True and False values. These are special values, and thus Spyder highlights them differently compared to other text, unless you mistyped them.

Strings are all characters encased in single quotes ‘ or double quotes “.

Data Types Exercise¶

Change the following inputs:

print(type('True'))

print(type(900.0))

print(type('9873.0'))

print(type('false'))

print(type(140 + 150.0))

print(type('754' + '987'))

print(type(100 - 50))

print(type(100 / 50))

To get the following outputs:

<class 'bool'>

<class 'str'>

<class 'int'>

<class 'bool'>

<class 'int'>

<class 'int'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'float'>

Doing simple algebra¶

Did the last few items throw you for a loop there? There’s more, but we’ll go over it from the beginning.

- Explore a bit and figure out how to do the following:

100 plus 100

200 minus 100

7 multiplied with 3

200 divided by 10

300 raised to the power of 20

Answer:

100 + 100

200 - 100

7 * 3

200 / 10

300 ** 20

All algebraic operations (plus, minus, multiply, divide) work as you know them. For raising exponents, use two asterisks **.

- Repeat the exercise, but make the numbers all floats this time.

100 plus 100

200 minus 100

7 multiplied with 3

200 divided by 10

300 raised to the power of 20

Answer:

100.0 + 100.00

200.0 - 100.0

7.0 * 3.0

200.0 / 10.0

300.0 ** 20.0

Notice that floats have the same interactions with mathematical operators as integers, i.e. you don’t need to bother about floats vs integers when it comes to getting math done.

- You do need to watch out for two things:

any mathematical operation involving floats will automatically convert the end product into floats.

all division operations result in floats regardless of input.

See for yourself.

print(type(100 + 100.00))

print(type(200.0 - 100))

print(type(7.0 * 30))

print(type(2000 / 10.0))

print(type(300.0 ** 20))

The above gives:

<class 'float'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'float'>

<class 'float'>

Now try and do the same thing with Booleans. Run the following code.

If any line throws an error, comment out the code by typing a pound sign before the code. This tells Python to ignore it. Our code examples will use comments from this point onwards.

# Mathematical operators on Boolean values

print(True + True)

print(False - False)

print(True * True)

print(True / False)

print(False / True)

print(True ** True)

If you are surprised, note that Python internally treats True and False as integers 0 and 1.

Now let’s do strings.

# Mathematical operators on strings

print('python' + 'is easy')

print("phone" - "no battery")

print('why is' * "wifi slow")

print("why are we" / "typing so much?")

print("when will" ** "class end?")

Any surprises?

Exercise: Python as a calculator¶

Use your phone or a online stopwatch to record the time it takes for you to complete this section. In the IPython console, key in the following. Press Enter after each line to run the code. :

%time 22/7

%time 31 * (1/3)

%time (7 ** 7) / (4 ** 9)

%time 355 / 113

%time (2143 / 22) ** (1 / 4)

The above code calculates the approximations to pi. Compare the time it took for you to key in the code, i.e. give the computer the instructions on what to do, and the time it takes for the computer to actually do it. What have you learnt?

Lists in Python¶

Let’s say we are observing weather data, more specifically the ambient temperature at noon every day. If we want to use this data inside Python, we will not create a variable for every temperature measurement that we have. Instead, we will deal with the data in bulk. One such data type in Python, is the list.

Explore the following:

# How to make a list

my_first_list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

# Lists can contain anything

my_second_list = ['a', 2, True, 4.0]

# What does printing a list look like?

print(my_first_list)

# List type

print(type(my_first_list))

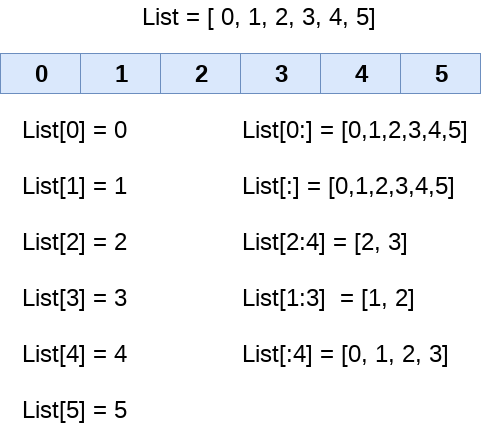

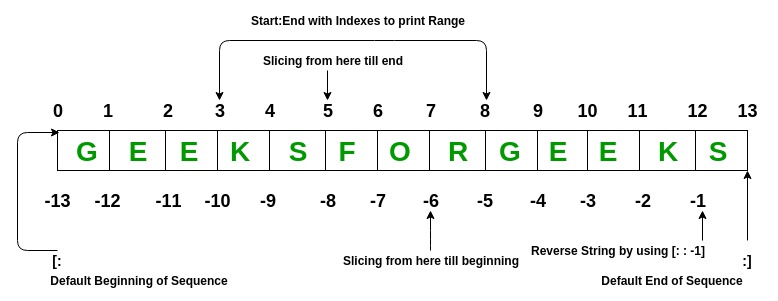

So now that we have information stored in a list, how do we use that information? We do something called list indexing.

List indices from https://yourpcfriend.com/python-lists/¶

Explanation on how this works from https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python-list/¶

Try for yourself:

# Print the first item

a = list('V', 'e', 'r', 'y', 'g', 'o', 'o', 'd')

# Print the second 'twinkle' and 'star'

b = ['twinkle', 'twinkle', 'little', 'star']

# Print just the last word

c = "Simon says go"

Example solution to the above:

print(a[0])

print(b[1], b[3])

print(c[11:])

Did you notice that variable c did not contain a list, but a string?

Final exercise!

# Make the code print:

# 'So,'

# 'actually strings'

# 'are'

# 'also'

# 'lists!'

d = "So, legend says that you can"

e = "actually take cello strings and"

f = "cook them. You are welcome! "

g = "By the way, you can also"

h = "list frogs for sale on Lazada!"

Conclusion¶

Take-away message for these week: Computers are a lot faster than humans at calculations. It is advantageous for us to phrase problems in code for computers to solve on our behalf :)

Further reading¶

- Textbook reference for this week: Python Crash Course: A Hands-on, Project-based Introduction to Programming by Eric Matthes.

Chapter 1: Getting Started

Chapter 2: Variables and Simple Data Types

Chapter 3: Introducing Lists

Learn more about the history of Hello, World: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/”Hello,_World!”_program

How print actually works in Python: https://docs.python.org/3.6/reference/datamodel.html#object.__str__

Following up, repr vs str methods: https://dbader.org/blog/python-repr-vs-str

A good resource explaining floating point numbers: https://floating-point-gui.de/formats/fp/

More on Boolean algebra: http://openbookproject.net/thinkcs/python/english3e/conditionals.html

Reference for lists: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python-list/